It is about: „Control and Care – Ambiguous Self-Relations and Life Maintenance Practices with Anthropomorphized Self-Tracking Technologies„

I would like to share my conclusion of this almost 6 years, that I’ve spent on reaesrach, data collecting, observing, interviewing, analyzing and modeling on the phenomenon of self-tracking and self-monitoring which is often contextualized with self-optimisation.

It is about balancing the control and care aspects in us when we try to maintain our lives in a best responsible way. It covers this dialectics of care and control, as self-affirmation, self-challenges and many more, and analyzes the role of technology for our self-relations, self-understanding and the drafting upon our identities.

Here’s the summary respectively my conclusion

This dissertation presents an analysis of the relations to self and technology that emerge from and in the use of self-tracking technologies to demonstrate and discuss further and, I argue, more significant technically mediated relations to self and technology, going beyond mere self-optimisation.

At the outset of this work, I linked to current cultural studies and sociological assessments of self-tracking as a self-exploitative travesty deeply rooted in neoliberal thinking, unconsciously heteronomous, launched by state and economic interests, which appears – or is intended to appear attractive to users under the sign of self-optimisation, as techno-optimistic groups, such as the Quantified Self network, and publications, such as in WIRED magazine, proclaim. Applying the analytical skepticism that Steve Woolgar articulated in STS as a pointed provocation, „It could be otherwise,“ my own ethnographic and auto-ethnographic treatment of the topic started from a different premise. I asked about the more profound experiences, logics, and dynamics in the encounter with these technologies and what they can tell us about contemporary human life and experience in a technologized world.

The self-relations made visible, addressed, and reinforced through the use of ST technologies can be subsumed under two broad themes: self-control and self-care. These two are addressed at one time each for themselves, but also appear simultaneously through a special ambivalent seeming and yet also concurrent existence.

While self-control is mainly characterized by awareness, a richer information base with higher decision-making certainty as well as goal control and adjustment, the self-care mode reflects softer factors such as turning to oneself, reflection, self-knowledge as well as enhancement or reinforcement of one’s self-image through positive feedbacks and self-overcoming. Thus, self-control initially appears as self-disciplining and self-education for self-improvement conditioned by externally determined system-relevant requirements. Complemented and mirrored by the self-care shown here, however, a turning towards oneself reveals, a focusing on one’s own goals: not working more but less, for example, not the highest goals (e.g. number of steps) but the goals that are right and important for me – in short, an intensified work on one’s own good feeling.

In a dialectical interplay (in the cognitive mode) Information, awareness, and complexity reduction on the control side interact with self-reflection, self-knowledge, and self-attention on the care side by providing uncertainty-reducing confirmations to prior hunches, relieving reminders, possibly future helpful detailed data for pattern recognition or treatments, and safety-providing orientation. In the action mode, proper goal setting, optimisation of work efforts, motivational incentives, and data-based algorithmic recommendations on the control side, together with self-affirmation, gratification, and emotional relief from supportive helpers, act as assistants in the seemingly infinite set of multi-optional choices for self- and life-regulation that should ultimately lead to balance and harmony in life.

We can understand the controlling collection of numbers and statistics about oneself as a taming (Hacking 1990) of insecurity and disorientation, even if it can take on an illusory character when viewed from an external perspective. Technology gives the feeling of getting a better grip on one’s life through it – as Ragnar has put it – and of achieving a relaxedness, as Arne has put it, simply by dealing with oneself in a „rational“, science-like way. Ultimately, it is about orientation and personalized / individual assistance in maintaining and caring for one’s life.

The empirical study has shown that self-control and self-care turn out to be two sides of the same coin. What they have in common is the constructive turning towards and confrontation with one’s own self, its goals, desires, strengths and weaknesses. The opportunities lie in strengthening one’s health and well-being in a playful way, building and maintaining a positive self-feeling, self-image and agency, and discovering unknown abilities and potentials within oneself. The difficulties lie in self-overload, dissatisfaction when not achieving goals, self-deception and distraction, narcissism up to loss of control – internally through compulsion to control as well as externally through loss of data protection and exploitation of private data by third parties as well as handing over responsibility (in the form of decisions) to technology (algorithms) instead of self-responsibility. The compulsion to self-control is interestingly mirrored by a commitment to self-care in the sense of a happiness imperative – happycracy – , as aptly diagnosed by Illouz and Cabanaz (2020). It is regraded as imperative to create the best version of oneself, regardless of the fact that social problems are shifted into the private sphere in the process. However, this is not an inherent characteristic of ST technologies, but is found in society as a popular trend towards the use of self-help offers, life coaching, meditation and yoga retreats as well as neurobiologically more profound interventions such as mood enhancers and concentration pills (nootropics) – as has been noted for years in academic writings (see Ziguras 2003, Traue 2011, Cabanaz & Illouz 2019).

The motives of the users that became clear in the course of the study – namely: to use convenient tools to manage sports or work activities, to deal with a chronic illness, to combat dissatisfaction with a condition or behavior in oneself, or the curious search for dormant potential in oneself – show the most evident starting points for the beginning of an ST application.

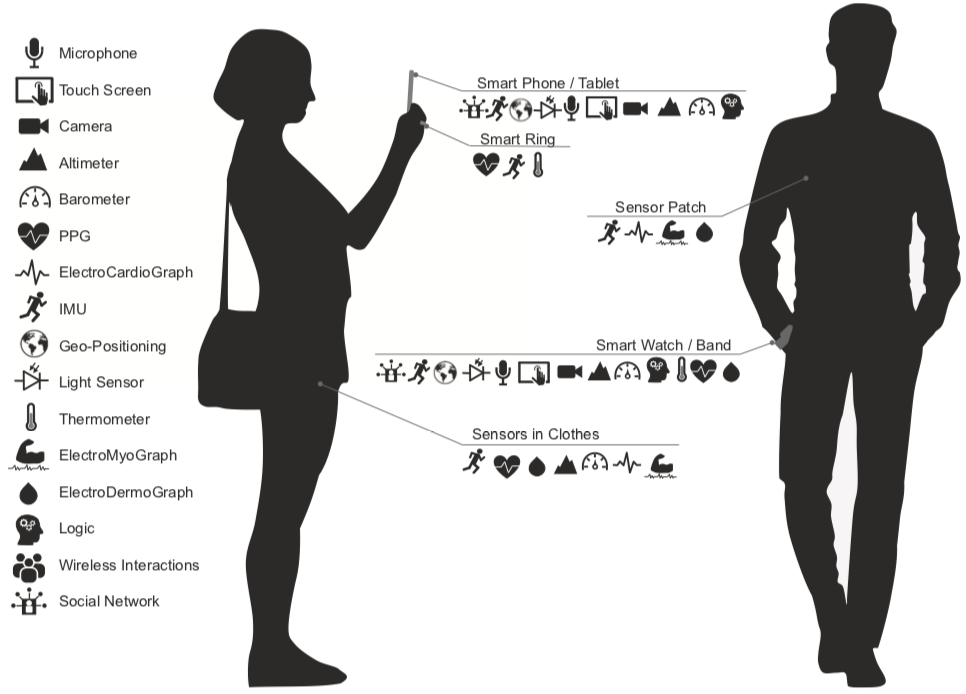

Meanwhile, the self-relations described in this paper are set in motion by the ST technology (and practice) used. Why? Because this technology, like any other technology, represents / contains a promise. It is the promise of easier self-improvement through its use as a smart tool that accurately records, stores, compares, visualizes, and analyzes infinite quantities. The sensors used in this assemblage (e.g., accelerometer, galvanic skin response, ballistocardiograph) often provide a sense of enhancing or sharpening one’s five senses. The apps used provide complexity-reducing visualizations, highlight patterns, and show trend progression. Built-in „coaching“ functions provide algorithmic recommendations, often based on big data, but customized and linked to our identity, on how to proceed in order to achieve the respective objective or improvement. This increases orientation and decision-making certainty and thereby ontological certainty (Giddens 1991) in life. The promise can even grow into a promise of salvation if it meets with corresponding hopes on the part of the user to cure an illness, to realize a long-cherished goal, or to acquire a skill that one did not possess before. People in secularized societies who take over responsibilities for themselves that were formerly anchored in the state and the social into their own hands can tend to look for the support that has fallen away in the technology or at least to hope for it – as Florian suggested. The design and functionality of ST apps and wearables in particular make them well-suited to take on a more intimate role for the user. Intimacy (pronounced differently: in-to-me-see) seems particularly appropriate to denote this new role of digital technology and our relation to it. By learning about and adapting to the user’s individual circumstances, personalized feedback and tips to improve a condition, joyful encouragement, as well as continuity and constant availability, digital assistants become emotionalized and sometimes anthropomorphized / personified. This increases a confidence in oneself and relaxedness in relation to one’s own environment of action. This was particularly evident in the remarks of the two women in my self-tracker sample, Karolina and Tabea, who also tended to talk about their ST gadgets using the personal pronoun „he.“ Which by assumption promotes self-satisfaction and leading a good life. From my point of view, it is to be expected that the relation to digital technologies will become more and more intimate and, so to speak, co-evolve with the maturing of the matter or technologies.

Also in the relations to technology, I think a dialectic is visible, which shows the apparent contrast between its conception as a tool and means to achieve something and the approach to technology as a counterpart, moreover as shown above an intimate counterpart – like a friend, partner or nanny – whose advice and continuity is appreciated. This is not evident in all cases where ST is used as a tool for pure measurement and recording, but certainly in those where lifestyle is significantly influenced. Like in Florian’s example who puts his hopes for a cure for his chronic physical ailments in a tool for measurement, storage and correlation analysis of personal data. Or Isger, who bases the way he lives his life, in the sense of guiding and structuring his day, on what the measurements of his answers to questions he compiled himself, together with his own analysis of the data, yield for him. In this way, ST Tech provides a rational basis for an emotional premonition or even longing for a work-life split that is sustainable for him. The realization and the decision to do so is then approved or as can be more aptly expressed in German „blessed“ by the technology. Here I understand the relation to technology as Heilsversprechen (promise of salvation) as a relieving legitimation, which counteracts possible feelings of guilt or shame, as it was often the case with myself. Ragnar also sought to resolve his stress-related speech problems in meetings through the use of ST technology. They advised him to do various relaxation exercises or encouraged him to look for alternatives to physical participation in meetings. This supportive „behavior“ of the ST Apps reminds us again of a caring partner who accompanies us continuously and without signs of fatigue.

Finally, the results indicate that the concept of (self-)optimisation, contrary to its etymological meaning of a logic of increase, can also be understood in a different way, namely balancing. In this context, optimisation does not necessarily mean the fastest, the highest, the strongest that is to be achieved, but that which is achievable and satisfactory for the self – within the framework of the given and the desired. Of course, there will still be individuals who accept the optimisation and self-responsibility imperative for themselves. Nevertheless, the self-reflection often stimulated and implied by ST technology can have a relativizing, individualizing, and sometimes disputing effect on common norms with respect to one’s own objectives. A study could subsequently be conducted on this and continue the debate on how optimisation is understood in society and how it is distinguished from improvement and enhancement – as drafted by the computer pioneers Licklider (Man-Computer-Symbiosis) and Engelbart (Augmenting Human Intellect) in the 1960s. Finally, further ST research could contribute to the figure of the cyborg discussed in the posthumanist and transhumanist research field.

This intensification in human-technology relations can currently also be observed in other areas. The digital voice assistants in our smartphones and smart objects, such as Siri, Alexa, Google Assistant, Cortana or Bixby, are taking on the role of personal nanny or servant. However, the field of self-tracking seems to me to be even more predestined for building more emotionalized, intimate, and partner relationship-like relations with technology. Engaging with a self is different than engaging with the weather, traffic, or shopping. Because it is more personal, digital self-tracking engages more profoundly and touches us more, and can shape and change us more than non-digital self-care techniques, such as psychotherapy or meditation – whether more sustainable can only be shown in a few years and appropriate research. On the other hand, technological promises, such as the promise of salvation, which is currently also being made in the debate on AI and machine learning, can be misused and tempt providers, developers and designers of corresponding digital assistants to overshoot the mark and make promises that serve only their own economic well-being and not so much that of the users. The hopeful customer would thus covert into a lifelong customer whose goal of improvement can and should ultimately never be achieved. Corresponding ethical guidelines on the part of government and economic actors are needed here. At the same time, the optimisation understood as harmonizing and balancing in self-tracking becomes a life task which, in principle, can never be completed. Because with the addition of new important areas in life and in the progress in the life time often also the individually understood and conceived balance shifts. Thus, in principle, new areas of improvement are always added. Until one gets out of the improvement cycle and says: Stop now – that’s good enough.

You can read and download the study on Academia or Researchgate.

You can cite my work in the following way:

Krzeminska, A. (2021). Balancing care and control an ethnographic study on self-tracking relations. Leuphana University. Retrieved December 24, 2021, from https://pub-data.leuphana.de/frontdoor/index/index/docId/1207. https://doi.org/10.48691/j6mz-bk87

Always happy to hear your thoughts on the subject and discuss them 🤓.

Du musst angemeldet sein, um kommentieren zu können.